Blueberry diversification spreads risk for arable farmers

15th May 2024

In a bid to build a sustainable business for their children, arable farmers Peter and Zoe Mee diversified into growing blueberries in 2014 – and have since installed their own packhouse and introduced a range of blueberry products made from waste fruit. Deputy editor Sarah Kidby spoke to the family to find out more.

For Peter and Zoe Mee, making farm improvements is always done with their children in mind. To spread risk and grow a sustainable business for the future, they diversified into blueberries 10 years ago, after two decades farming arable land in the Nene Valley, Northamptonshire. Although it was a huge capital investment, the diversified crop reduces their reliance on arable income streams whilst making use of their existing irrigation licence – a very valuable asset that was previously unused.

Mix of early and late varieties

All fruit that meets the grade is sold fresh in major supermarkets through Driscoll’s UK – last year it went into M&S, Waitrose, Lidl and Morrisons. The first variety grown at the farm was Liberty, a late season variety chosen for its flavour.

Another late variety, Driscoll’s Barbara Ann, grows berries around the size of a 20–50 pence piece, and has a slight blackcurrant note to the flavour, while the farm’s two early season varieties are the high-yielding Duke, with a traditional blueberry flavour; and Driscoll’s Sweet Jane, which offers a larger berry size and sweeter flavour.

One of the more recent additions is Peachy Blue. This variety fills a gap between the early and late varieties so the business can supply consistently over the British season, and it has a unique peach flavour. Meanwhile, Sekoya Crunch, developed to have a ‘crunchier’ texture – is the latest variety to be added to the farm’s repertoire, as a result of supermarket feedback that customers want a firmer berry.

While the Mees are always interested in new varieties, unlike the annual rotations with strawberries, blueberry plants can have a lifecycle of 10–20 years, so it’s a big decision and investment.

Key tasks

Primary tasks begin in February with pruning and recruitment for the summer season, followed by polytunnel building in late March/April. During April, May and June they keep on top of weeding, mowing and support structure maintenance, then picking and packing begins at the end of June/beginning of July and continues through to mid-September/October. All fruit is packed on-site and they aim to pick fruit on day one, pack on day two and for it to hit supermarket shelves on day three to keep fruit at optimal freshness where possible. Autumn time is for tidying up, going back through weeding, mowing and taking down polytunnels.

Much of the horticultural work – pruning, weeding and picking – is done manually. The farm’s key machinery revolves around the packhouse grading process, where fruit passes over a lift belt, optigrader and punnet filler, through a heat sealer, metal detector, check weigher, labeller and onto a lazy Susan collection table. Most equipment is second-hand, but smaller pieces of equipment are sometimes bought new.

The farm has three full time honeybee hives in the blueberry fields and another 10 on the arable land, maintained by local beekeepers. Each year they buy in 120 triple hives of bumblebees from Holland, which are filled with UK native bumblebees which have a natural lifecycle of eight weeks, making them perfect for the pollination window on the farm. This year they are trialling 25 honeybee hives with Apidae Honey, which moves its hives around the UK to aid pollination and keep bees fed on whatever pollen is in season.

Pest and frost challenges

The blueberry aphid (Ericaphis scammelli) is the farm’s primary pest problem, though they also see some potato aphid, melon cotton aphid and apple aphid later in the season. Its goal is to enhance biological control by not mowing grass margins to encourage beneficial insects such as hoverflies, ladybirds and aphidoletes. However, on a couple of seasons the aphid has come in large numbers all at once so an insecticide application with a mist sprayer was required. Additionally, nematodes are applied through a drenching system with large quantities of water, to control vine weevil in the roots of the plants.

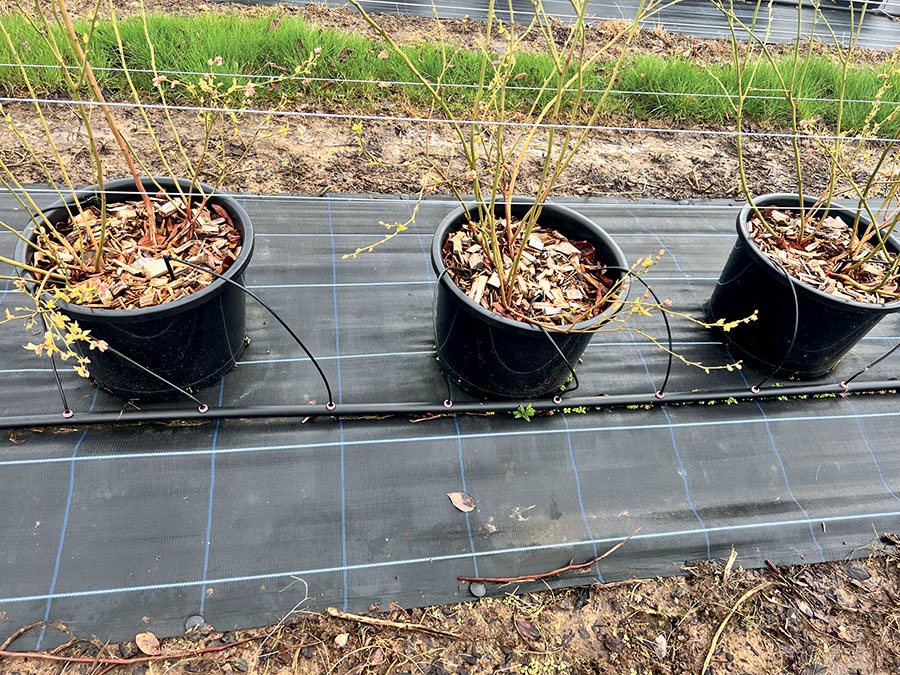

Whilst the arable business has adopted regenerative practices and has a large focus on soil health and testing, this is less vital for blueberries. The plants are in beds and pots of specially crafted composts to provide them with the acidic and ericaceous soils needed for their survival.

Blueberries need around 1,100 hours of chill time (sub 7ºC). Fortunately, the frost hours the farm gets are often within this dormancy stage over winter. Frosts in the spring have a less severe impact on the fruit if the polytunnels are up, due to the slight microclimate generated.

The farm has only experienced loss of buds/flowers a couple of times due to frost, so the cost of the available frost protection measures is not worthwhile at this stage. Fleecing or fans are also expensive solutions, so it’s hoped they can continue without these interventions.

Innovative solutions for waste fruit

Packing and distribution was previously done in Kent but installing their own packhouse in 2019 allowed the business to pick and pack all fruit on-site and control what happens to waste produce. Sustainability is key for the Mees, and since 2020, fruit that is ripe at the time of picking but does not have the required shelf life needed for British supermarkets, is used for the farm’s blueberry product line. This fruit is frozen on the same day it goes over the grading line to preserve its flavour and as much of its nutritional value as possible.

Branded Mee Blueberries, the range includes: Blueberry & Lavender Jam; Blueberry, Beetroot and Chilli Chutney; Blueberry Gin Liqueur; Blueberry Vodka Liqueur; 100% Natural Blueberry Fruit Juice and a Blueberry Sparkling Wine. The products themselves are made to the family’s recipes, by producers with the correct machinery and accreditations. Each of the farm’s producers is selected for their specific expertise, to achieve the best produce possible for their customers. The products are then taken back-in house to brand and market.

By using this grade of blueberry, stock is limited so these products are sold on the Mee Blueberries website, and through a few local farm shops, cafes, garden centres and village shops – as well as food markets and local events.

Meanwhile, any fruit that is underripe or has been damaged by insects, birds or mould is removed and goes to a local pig farmer.

Making the most of what they have and utilising key resources, is important for the Mees. As well as their award-winning sustainability efforts on the arable side of their business, their blueberry irrigation systems work through trickle irrigation systems, helping to keep the water waste on site very low. They are also using the Hortiplanet carbon calculator developed by Haygrove to help them work towards their net zero goals.

Sourcing labour post-Brexit and covid

The Mee family all farm full time – Zoe and Peter oversee all operations, particularly regarding fruit sales and grain stores, while their son Charlie manages the arable operations and his wife Charlotte does the bookkeeping and manages the packhouse. Their daughter Emily manages the storage operations in harvest and is responsible for the Mee Blueberries product line. The horticultural business employs one full time manager, while all other staff are seasonal. A small group of seasonal staff work from February through to mid-October helping with pruning, weeding and polytunnel building, but most join them at the end of June.

One of the farm’s biggest challenges is the reduced availability of staff and increased cost of labour, which has risen more than 28% in the last few years, from £8.91/hr in 2021 to £11.44/hr. Pre-Brexit and covid, the farm’s Bulgarian manager recruited friends and family from home, but only 12 of these workers are now able to return with pre-settled status as covid hit the final year of applications – and this only allows them to work for five years. Plus, with the farm’s busy season only lasting 3–4 months, it does not meet the six-month minimum per year needed to apply for settled status in the UK.

As a result, they have increased their advertising to target the UK job market, but unemployment is very low and, post-covid, catering and hospitality firms are now also recruiting from the same labour pool. However, as the farm’s harvest is mainly July, August and September, it hopes to work more closely with schools, colleges and universities.

The farm sponsored 12 Ukrainians after the war broke out in 2022, and a number have worked with them on the farm, though many have now moved on to long-term positions elsewhere. Last year, Mee Blueberries also used the government’s ‘Find a Job’ service and its own social media and website to recruit individuals with settled status, but has been unable to source its full staff in this way. Most staff are sourced through the Seasonal Agricultural Workers Scheme (SAWS); last year saw 32 members of staff join from Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan and it’s hoped they will return this season. However, the SAWS scheme has only been confirmed until the end of 2024, with no current proposals for the future.

Cost of living crisis

Demand can be unpredictable and the cost-of-living crisis paired with rising costs of production are another challenge for the horticulture business. While supermarkets keep customer prices as low as possible, they do not want to reduce their margins long term, so the grower takes the brunt of the cost increases.

“Blueberries have seen significant growth in demand in the last few years, however the consumer market is all about convenience – being able to purchase goods throughout the year, at the cheapest prices available,” the family explained. “Due to the labour-intensive nature of the blueberry growing process, it is difficult to compete with imports on a cost basis, when our minimum wages are significantly higher and our enforced environment goals are set to a higher standard than overseas producers.”

Rising cost of production has a significant impact on farm profitability, removing the ability to invest in the future, so the family is looking at alternative options. Their move to regenerative farming has been timely, saving money on machinery wear and fuel usage through fewer passes over the land, as well as reducing expensive pesticides.

The family is also looking to reduce its reliance on conventional power, by increasing renewable energy generated on the farm. It already has a ground source heat pump and 70,000kw of roof mounted solar panels.

What’s next?

With labour a significant challenge, Mee Blueberries is looking to bring new machinery into the packhouse to reduce staff numbers. Its blueberry picking is currently done completely by hand and whilst the family is looking at automation and robotics, and is open to trialling mechanical harvesters, these are not currently a viable option.

On the product development side, however, the business has just launched a new blueberry balsamic vinegar in April. Whilst further diversification is appealing to the family, time is the main barrier.

Grower Profile

Farm owners: Peter and Zoe Mee

Location: Lyveden Farm, Peterborough

Total farm size: 245ha arable, 15ha blueberries

Varieties grown: Duke, Liberty, Driscoll’s Sweet Jane, Peachy Blue, Last Call, Driscoll’s Barbara Ann, Sekoya Crunch

Soil type: Plants grown in compost beds have a compost mix of: green waste, pine bark fines and pine bark chips. Plants grown in pots have a compost and peat mix

Read more fruit news

Read more grower profiles