Is low and no alcohol wine the future?

1st April 2025

Retailers are reporting a growing demand for alcohol-free drinks – but producing quality low and no alcohol wine presents challenges. Sarah Kidby spoke to the experts to find out if a zero alcohol English wine could be on the horizon.

With an increasingly health-conscious population – and a younger generation that consumes far less alcohol – the popularity of low and no alcohol wine has risen significantly.

At the end of 2024, Tesco reported 10% growth in sales of its low/no alcohol wines – with sales of Kylie Minogue’s 0% sparkling rosé seeing a boost of 70% compared to the previous year.

Sales of low/no alcohol drinks in general rose during 2024, including, unusually, during the summer’s Euro 2024 football tournament.

Similarly Waitrose now has over 15 ‘low and no’ options available and saw sales increase by 19% over the past year – and not just during typical times of year such as Dry January.

It’s becoming a year-round trend, according to Waitrose low and no alcohol buyer Sarah Holland.

Meanwhile, Wednesday’s Domaine is bringing a selection of its alcohol-free wines to Ocado for the first time this year – Piquant, a still white; Cuveé, a sparkling rosé; and Vignette, a full- bodied red. The business saw its monthly sales in December eclipse its previous best by 120%.

Even some French wine producers are beginning to openly contemplate alcohol-free bottles – which not long ago would have been unspeakable. Les Belles Grappes, Bordeaux’s first ever cave – wine shop – dedicated to no/low alcohol wines opened in November.

But despite its rising popularity, low/no alcohol wine presents significant challenges when it comes to production – particularly for English wine, as the commercial industry is still relatively young.

Creating a consistent product that is a facsimile for wine, but with zero alcohol, comes with loss of flavour, aromas and preservative ability when the alcohol is removed. So, can it be done, and is it part of the future?

READ MORE: New English wine brand uses fresh techniques to grow non-traditional varieties

READ MORE: Wine industry boss reacts to Spring Statement

What methods are used?

Dr Akshay Baboo, resident oenologist at Plumpton College, believes the low/no alcohol category will catch on quickly – particularly in light of the ongoing cost-of-living crisis, as there is negligible duty on low alcohol wine, and zero duty on no alcohol wine.

After wine has been produced using traditional methods, alcohol is subsequently removed to produce low/no alcohol wine. Commenting on the challenges, Dr Baboo explains: “Alcohol is a fantastic solvent, meaning that it dissolves flavour compounds rather well.

“And the trouble is when you try and take out alcohol, unfortunately these aroma compounds are also taken out at the same time which means that to balance the mouthfeel and flavour you’ve got to add 3–5g of sugar per litre, and then a load of flavourings or stabilisers because alcohol is also a fantastic preservative.”

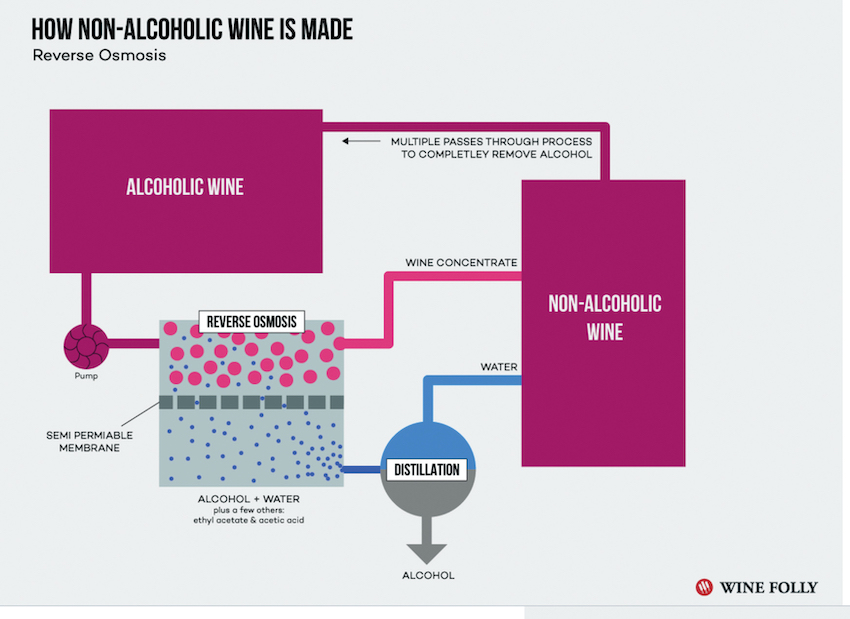

Reverse osmosis is a “fantastic way of removing alcohol”, he adds, or alternatively, producers can use a spinning cone device – which is like a centrifuge but with every alternate plate spinning at very high revolutions per minute.

This strips the alcohol from the wine as it has a different density to water. Dr Baboo compares the process to pulling cream from milk.

Wine consultant Charlie Holland notes that these machines are generally large and expensive, however, so certain volumes and economies of scale are needed to justify the cost.

“Given the relatively high costs involved in making English wines before dealcoholisation, and the generally smaller volumes produced by English wine producers, this can make the process inhibitory,” he adds.

While the demand for low/no alcohol wines is there and the future looks bright for the category, Mr Holland argues that advancements in technology and taste are needed for it to become mainstream.

A considerably less attractive option for removing alcohol is dilution with water which would be done to the juice before fermentation, Dr Baboo says. However, it means the acidity is no longer in balance and acid will have to be added. Distillation is another possibility but the wine becomes tainted due to heat.

Available additives

Additives, including dimethyl decarbonate (trade name Velcorin), can be used to combat the loss of flavour and preservative when alcoholWisinreSmecorvetesd.

Whilst this is a “fantastic product” that ensures stability with minimal taste or flavour ramifications, the downside is that it’s highly corrosive and must be kept at the correct temperature and dosed in exactly the right way, Dr Baboo warns.

This means investing in expensive kit – if the temperature drops the additive will freeze and become useless, while if it gets too hot it’s incredibly flammable.

Velcorin is safe for consumption in the quantities added to wine, but the above factors make it prohibitively expensive for English wine producers, he adds.

Other options include increasing the amount of sulphur dioxide – not, of course, above legal limits, which would make the wine undrinkable in any case.

Or, adding standard preservations such as potassium sorbate, which is found in most fruit juices and products that require a reasonably long shelf life. Again, there can be flavour implications.

A halfway house

Due to the aforementioned challenges, Dr Baboo believes low alcohol wine, between 3–6%, offers the best ‘halfway house’ and is a more feasible way forward for the English wine industry, retaining some of the wine’s flavour and preservative ability, whilst still significantly reducing alcohol content.

“That’s where the real potential, at least in my opinion, lies because you have the best of both worlds – you have the protective influence of alcohol,” he states.

With a standard bottle of 12.5% wine containing 10 units of alcohol, reducing this by half could offer a significant benefit to those wanting to reduce their alcohol intake for health or other reasons, and there is a better chance of retaining the aromas and flavours.

However, it can be more difficult to market something that is low alcohol rather than zero alcohol, in much the same way that it’s easier to market a zero-sugar product than a low sugar product.

READ MORE: Could Trump impose 200% tariff on alcohol from EU?

READ MORE: Will drinkers be won over by Scandi wines?

Need for alcohol regulation

Leaving aside the consumer demand for low alcohol, Dr Baboo believes that finding ways to regulate alcohol levels could become a necessity for some English wine producers.

The changing climate means there are wineries in the UK that are already naturally producing

14% alcohol wines in warm years such as 2023, without adding sugar.

This is a concern, as once you start to go above 13.4–14%, alcohol becomes the overriding flavour.

“Wines do feel hot and lack acidity, and in general wines start to lose that balance. From a winemaker’s perspective, it is also good to have the ability to regulate the alcohol,” he comments.

Reducing the alcohol levels does not mean that growers can pick any earlier, however, as weather patterns in the UK prevent this.

Meanwhile, more established wine regions such as France, Italy and Spain have had a couple of decades to come up with mitigations for higher alcohol content.

For example, Bordeaux and Champagne have allowed newer or hybrid varieties to help tackle the issue. With the English wine industry having been commercially viable for perhaps only 15–20 years, producers have not had this time to acclimatise, Dr Baboo notes.

What might the future hold?

Despite the challenges, it’s clear that there’s a market for low/no alcohol wines which the English wine industry could capitalise on – should the technology allow.

Wednesday’s Domaine founder Luke Hemsley noted the similarities between English wine and no/low alcohol wine – both once ‘fringe’ products that have become beloved by customers, there’s a lot they can learn from each other, he reckons.

Asked if he sees a future for low/no English wine, he says: “I have no doubt that we will; however, I suspect this will be as much a product of where producers choose to focus their energies as their capability to do so.

“There remains a huge opportunity in developing the [alcoholic] English wine industry and I suspect producers will be mindful of spreading themselves too thin and diluting their messaging as consumers just begin to engage with their wines at scale.”

Organisation such as Plumpton and NIAB are currently researching methods of reducing alcohol content in English wines, but details are strictly under wraps for now – so for the moment, watch this space.

Read more drinks news.